We have taken to measuring our children’s success repeatedly

and then using that data to assess how we are teaching, who is teaching, where

funding should go and other important aspects of our education system. This sounds, on paper, like a great idea –

get the data and then respond to reality. So how could this go wrong?

Well, first, there is the experience of being tested to

contend with. Each test gives us

information about how students are doing – but the test is another educational

experience, as well. And that experience

affects our children. What does it feel

like, at the age of 5, to be just starting school and begin with a test? And, since it is a baseline test, you are

expected to fail it. And you do.

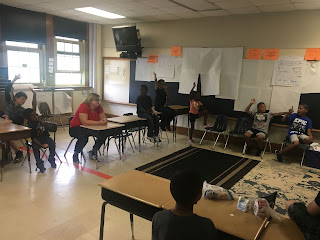

And you’re five. One kindergarten teacher described her students’ response: “They don’t know how to hold

pencils. They don’t know letters, and

you have answers that say A, B, C, or D and you’re asking them to bubble in. .

. . They break down; they cry.” Research shows that these tests can decrease

students’ love of learning (Jones et al., 80).

They may score well on a test, but also learn to dislike school. And the level of anxiety high-stakes testing

produces can make many students physically ill, with incidents of stomach aches

and headaches skyrocketing on test days (Jones et al., 95). Testing and the anxiety that accompanies it often

leads to lower scores (Cassady and Johnson 273), which then increases test

anxiety for the next test, creating a destructive cycle. Ironically, our measurements of how well our

students are learning may show less achievement than they would be capable of

without these measurements.

Second, there are limitations to what we can measure on a

standardized test. A multiple choice

instrument is not conducive to measuring creativity and imagination. You cannot see how a student arrived at an answer.

But, since more qualitative measures are difficult to score, we opt for

bubbling in A, B, C and D. These

multiple choice questions are best suited to lower level thinking skills like

memorization and description. Higher

level thinking like analysis and evaluation are difficult to test by choosing

one of four offered answers. Even memory

is not well tested by multiple choice, because the answer is written out for

the student and all she has to do is find it in the list – rather than recall

it herself. And don’t forget that a student

may have guessed the correct answer.

Standardized tests do not give us a window into the thought-processes of

students. As teachers, our goal is to

meet students where they are struggling and help them figure out the material,

but a score on a standardized test does not give us the information we need to

do so.

So what are children achieving when they score well on a

standardized test? They have prepped

well, their teacher has drilled them on the facts they need to know to pass the

test, and they have good memories. This

does not tell me if the student has new, creative ideas or if he is engaged by

reading The Giver or if he

understands the causes of the Civil War.

Albert Einstein once complained that coercive testing so turned him off

to learning that he gave up on science for a year. Are we losing some young Einsteins because of

our current emphasis on high stakes testing?

Bibliography

Cassady, Jerrell C. and Ronald E. Johnson. "Cognitive Test Anxiety and Academic Performance." Contemporary Educational Psychology. (2002) 27:270-295.

Jones, M. Gail, Brett D. Jones, and Tracy Y. Hargrove. The Unintended Consequences of High-Stakes Testing. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2003.

Monahan, Rachel. "Kindergarten gets touch as kids are forced to bubble in multiple choice tests." New York Daily News. 10 Oct 2013.

"Multiple Choice Tests." FairTest. fairtest.org. 17 Aug 2007.